Originally published in The Otter.

By Jessica DeWitt

|

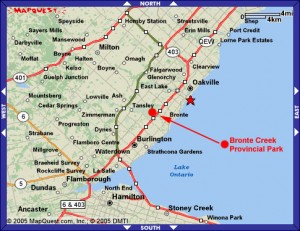

| Location of Rouge Park; Source: Canadian Geographic/Chris Brackley |

CHESS’s Saturday excursion into the suburban wilds originated at the

Markham Museum, a Toronto suburb located north east of the city. Our

visit began with a presentation by two Parks Canada employees on the new

Rouge Urban National Park initiative, which will be the first Canadian

national park located within an urban setting. Rouge Park was initially

created in 1995 and is currently made of 47 square kilometres of

provincial and municipal land. With the creation of Rouge Urban National

Park, it is expected to expand to 58 square kilometres. (For more

reading on Rouge Urban National Park see the July/August 2013 issue of

Canadian Geographic, which contains an excellent

article

on the park). The Parks Canada staff emphasized a few main points.

First, the new urban national park is being created by the Canadian

government to meet rising demand for accessible outdoor recreation.

Rouge would be the first national park reachable by public transit.

Second, they emphasized the green belt function of the park, a mechanism

by which to preserve and restore the last remaining sections of

green-space in the Greater Toronto Area. Third, they discussed the

park’s relationship to the farms located within the park boundaries–a

relationship that is either idyllic or fractious, depending on who you

are talking to.

|

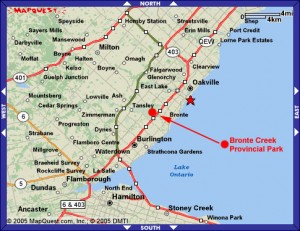

| Location of Bronte Creek Provincial Park; Source: brontecreek.org |

What struck was that I had come across all of these arguments before.

The rationale for park creation is nearly identical to that of Bronte

Creek Provincial Park, in Oakville, Ontario, halfway between Toronto and

Hamilton and just off of the Queen Elizabeth Way. The preeminent

landscape feature is the Bronte Creek Ravine, which crosses the centre

of the park and reaches a depth of 150 feet. Bronte Creek was created in

1971 from five separate family farms and it represented the first

concrete manifestation of the Ontario government’s 1970s fascination

with the near-urban park concept. It acted as a catalyst for other

near-urban park initiatives in Ontario, including London’s Komoka

Provincial Park and St. Catherine’s Short Hills Provincial Park. Other

provinces had their own near-urban park projects, such as Alberta’s Fish

Creek Provincial Park in Calgary.

The objectives of Ontario’s near-urban park enterprise can be broken

down into two categories: environmental considerations and the further

democratization of recreation. On the one hand it was hoped that parks

like Bronte Creek would siphon off some of the visitors from more

primitive parks, like Algonquin and Quetico, thus protecting them from

the threat of over-use. Near-urban parks were also meant to save the

last remaining remnants of green-space from urban sprawl, functioning as

part of a city’s greenbelt and acting to drive further conscientious

land use planning. On the other hand, near-urban parks were meant to

make outdoor recreation more accessible to urban populations. Provincial

park accessibility hinges on the availability of automobile transport

and cheap fuel, both of which were increasingly elusive for most of

Toronto’s citizens during the 1970s.

|

| Bronte Creek Ravine |

|

| Henry C. Breckon Demonstration Farm |

In 1971, Premier William Davis commented that Bronte Creek

represented a “dramatic departure from the established concept of

provincial parks [that] promises to bring the pleasures and beauties of

our natural environment closer to a large number of city people.” (Marsh

4) It was to provide day-use opportunities to the 1.5 million people

who lived within a 40 kilometre radius of the park. 6,000 parking spaces

were provided and the park was designed to handle 30,000 visitors a

day, 15% of whom were expected to arrive by public transit. It was the

first provincial park to design facilities specifically for disabled

people. Original plans created separate recreational zones designed to

protect more fragile areas of the park. Efforts were made to restore the

creek valley, including reforestation and wetland restoration. These

restorative efforts occurred alongside efforts to replant orchards,

fields, and other plants that had been present during the land’s

agricultural heyday. Two of the farms were restored and used as a

children’s farm and a demonstration farm, which was to represent

turn-of-the-century mixed farming in Ontario.

|

| Two Handsome Cows -Residents of Bronte Creek Provincial Park |

|

Bronte Creek and other near-urban provincial parks represent a

takeover by the provincial government of what was traditionally a

municipal responsibility: providing recreational opportunities for urban

residents. What occurred in Ontario and North America more broadly that

made this shift occur? Does the contemporary takeover of this

responsibility by Parks Canada with the Rouge Park initiative represent

another notable shift? It should be noted that in some ways the

near-urban provincial parks were a failure: they never reached the level

of popularity that was initially expected. Much of the elaborate

original planning for Bronte Creek, which included a tram system, was

never realized. The entire near-urban park initiative was basically

canned by the late 1970s, when a conservative government came into power

in Ontario and deemed the concept not worth pursuing further. Does the

creation of Rouge Urban National Park illustrate the failure of Ontario

Parks to meet urban outdoor recreation demand? Or does it represent a

resurgence of the same societal pressures that led to Bronte Creek

Provincial Park in the early 1970s? Comparison of the two parks raises

such questions as these. The parallel origin stories of Bronte Creek and

Rouge Park further illustrate the importance of looking to the past to

more fully understand the implications of our current actions.

Sources

Walter H. Kehm, “Near-Urban Parks: What Are They?”

Park News 13 (1977): 8-16.

Gerald Killan,

Protected Places: A History of Ontario’s Provincial Park System (Toronto: Dundern Press Limited, 1993): 213.

Ellen Langlands,

Bronte Creek Provincial Park Historical Report, December 1972.

John Marsh, “Near-Urban Parks,”

Park News 13 (1977): 2-7.

Project Planning Association Limited,

Bronte Creek Provincial Park Demonstration Farm Report, Bronte Creek Provincial Park, 1973.

The grounds are lovely – a perfect place for lunch and a coffee!

The grounds are lovely – a perfect place for lunch and a coffee!